Surviving Pandemics: Merchant Taylors' and the Plague

Given that Merchant Taylors’ School was founded in 1561 at Suffolk Lane in the heart of the City of London, it should come as no surprise that the school has endured several epidemics in its long history. In fact, records suggest that the school had to cope with outbreaks of plague in 1592, 1603, 1626, 1630, 1637 and 1666.

In 1592, the school closed in response to an outbreak and perhaps the biggest consequence of this was that the newly appointed Head Master, William Smith, was immediately ‘dismyssed for this tyme vntill the schollers be drawen togeather agayne’. One can only assume that in the absence of any fee-paying scholars the Merchant Taylors’ Company exercised financial constraint without the benefit of any government furlough scheme.

In 1603, the plague was particularly virulent and the Head Master, William Hayne, sought the opinion of the Company on whether he should shut the school. The Company’s reply that ‘The Company houlding him to be A man of Judgm.t doe referre the same wholly to his own discrecon, And what he shal thinke fytt to be done the Company will allowe’. Such a response suggests that the members of the Company had already headed for the countryside as did most of the Scholars, despite this Hayne (possibly learning from William Smith’s experience) decided to keep the school open. This led to a major loss of income for Hayne and he had to petition the Company for help, which they gave in the form of a grant of 20 marks – worth approximately £4,500 today.

The plagues of 1626 and 1630 had similar effects, the school’s pupils stayed away and the Head Master, Nicholas Gray, wrote that he was ‘forced to discontinew & give over for that tyme’. The Court’s records suggest he was compensated with £20 on the first occasion at least. For the pupils, there was the concern that the Fellows of St John’s College, Oxford would not visit the school to elect scholars from the school to the college – though the 1566 statutes of the college suggest that these elections could be held in some place not far from the City.

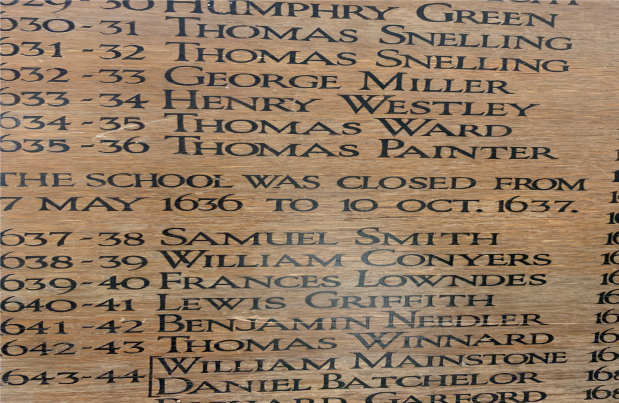

Perhaps the most significant impact of the Plague was felt when the school had to close between 17th May 1636 and 19th October, 1637. This fact can be seen on the list of Head Monitors by the stairs to the Great Hall. The school struggled to survive – no pupils joined the school until December 1637 when 33 scholars joined. It seems clear that the Company helped the school pull through, the Head Master William Staple, received grants totalling £140 in five instalments – something like £16,500 in modern value. Even though the school was shut, Staple was praised for keeping the head form together – the Sixth Form – and giving them regular instruction without a precaution. This enabled four pupils to be elected scholars of St John’s College. Nevertheless, once the school reopened the Company had to dispense with the Deputy Usher (or Deputy Head) who sulked at the lack of promotion to Head Master following Staple’s own departure.

Perhaps the most significant impact of the Plague was felt when the school had to close between 17th May 1636 and 19th October, 1637. This fact can be seen on the list of Head Monitors by the stairs to the Great Hall. The school struggled to survive – no pupils joined the school until December 1637 when 33 scholars joined. It seems clear that the Company helped the school pull through, the Head Master William Staple, received grants totalling £140 in five instalments – something like £16,500 in modern value. Even though the school was shut, Staple was praised for keeping the head form together – the Sixth Form – and giving them regular instruction without a precaution. This enabled four pupils to be elected scholars of St John’s College. Nevertheless, once the school reopened the Company had to dispense with the Deputy Usher (or Deputy Head) who sulked at the lack of promotion to Head Master following Staple’s own departure.

Interestingly, the Great Plague of London (1665) gets very little mention in the records of the Merchant Taylors’ Company. The diarist Samuel Pepys noted that the Plague reached London on 10th June and the school held its normal St Barnabas ceremony on June 11th, and fifteen boys joined the school. No-one joined thereafter until March 1666, when 11 boys joined. However, the great disaster of the Fire of London was just around the corner and there were no further enrolments until March, 1670. The heroism of the Headmaster, John Goad, in saving the school’s precious library of books (still in the school’s archive today) and keeping the school going is a story in itself and best saved for another day.

The school survived a turbulent century where epidemics were an existential threat to its existence. By the 18th century Plague had diminished, so that in 1731 Daniel Defoe was to write ‘Merchant Taylors’ School is situated near Cannon Street, on St. Lawrence Poultney Hill. This school, I am told, consists of six forms, in which are three hundred lads, one hundred of whom are taught gratis, another hundred pay two shillings and sixpence per quarter, and the third five shillings per quarter; for instructing of whom there is a master and three ushers.’