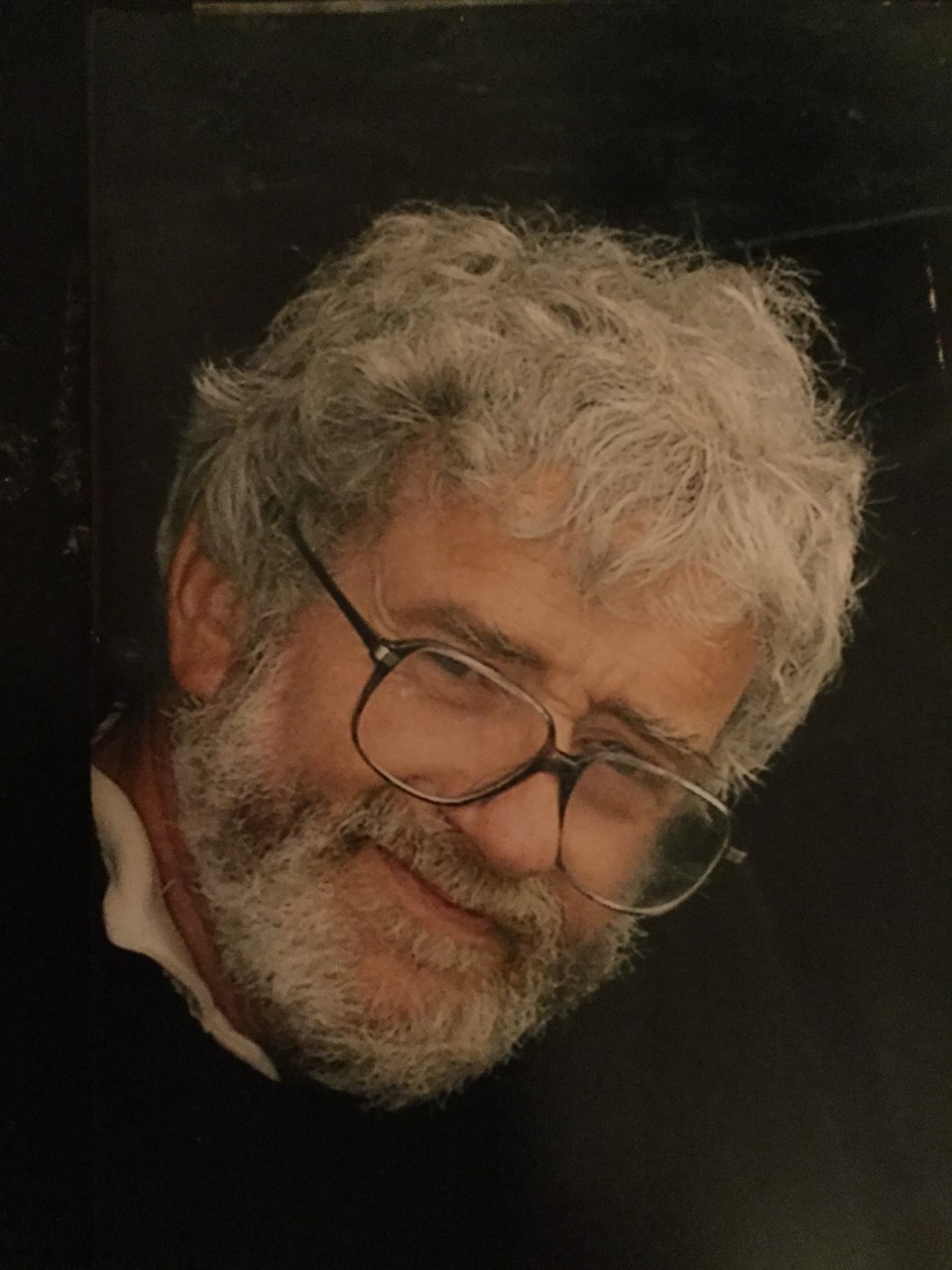

Stephen Richard Henig (1958-1963)

Died on 10th September 2020, aged 76

From the moment that I can first remember Stephen as an infant, just over two years younger than me, he was lively, irreverent and always bursting with humour and human warmth. We lived in Eastcote, North-West Middlesex, where our father was a local GP and the house was always full of books and lively conversation and argument- and Stephen certainly could argue! His intelligence shone through, often in zany ways, in the stories he told throughout his life of contacts with schoolteachers, lecturers, and colleagues, always hilarious and full of understanding and warmth. I never heard him being malicious about anybody.

At Wellington Preparatory School in Hatch End, he was happy and gregarious and there he made his two closest friends who remained friends for life. Showmanship came naturally to him and at childrens' parties - which at that period always featured jelly and blancmange – he would as an 8-year-old star perform as the conjuror to fellow classmates.

He enjoyed his time at Merchant Taylors’ in some ways rather more - at least it was largely sane and mainly civilised while Wellington had an unpredictable and sometimes violent headmaster. Even the CCF was more fun for him than it was for me. His clowning won the heart of the kind- hearted Sergeant Major, Arthur Bell and his wife so he dodged parades and took Mrs Bell shopping instead.

Academically, he only really shone at school in English, inspired by the teaching – which I had also been privileged to enjoy a few years earlier – of Harry Hunter and especially John Steane who deepened his already quite extensive knowledge of drama (thanks to our parents’ passion for the theatre) and especially opera,which he discussed enthusiastically with John Steane, an authority on both Elizabethan plays and Italian opera. At that time we seemed to go often together to the theatre or the opera in London every week, thanks to cheap evening fares. That wide knowledge stood him in good stead, when some years later he applied for, and was accepted, to read English at Bangor in North Wales, by Professor John Danby, author of Shakespeare’s Doctrine of Nature.

In the meantime, after leaving school Stephen went to work at Waring and Gillow where he was able to employ his humour and charm to great effect on the sales floor, being additionally inspired by handsome commission rewards for his excellent sales figures. But at home he regaled the family with hilarious but kindly stories about his colleagues and customers which made his day job sound thoroughly entertaining. Nevertheless, it did not satisfy Stephen, who went to a crammers to get his A levels, and then, waiting to go up to Bangor taught for a term in a primary school, dramatizing Robert Graves’s I Claudius with flair and imagination. He was also a star actor himself in a local drama group, The Vikings, which performed Medieval and Classic plays in local churches and church halls. He was brilliant as Everyman, in the Late Medieval Morality play, pulled out of the audience to justify his life.

At Bangor he did well, running the English Club and inviting distinguished guests, one of them John Steane, who exchanged the relative calm of Moor Park, for a North Welsh blizzard in which both of them were almost lost in a snowdrift.

After Bangor he took his Post -graduate teacher’s training course at Bristol, run by ‘Pat and Norm’ a couple with advanced and sometimes eccentric views, very concerned that children should not be overstretched, and rather censorious of academic excellence. Stephen’s social heart was, of course, with them but he found their obsessive seriousness very amusing and they became stock characters in his anecdotes. Stephen always believed that one of the keys to education was giving pupils from whatever background an enduring love of knowledge and sense of achievement. He taught in a number of schools. He gave confidence to a number of highly intelligent pupils from relatively deprived backgrounds, setting them on the path to university and high achievement, but even more typical was giving students regarded as failures a sense of their worth through a friendly manner. There were interesting incidents. On one occasion in a school near London Airport, he had locked himself out of his car at the end of the day. One of his students sauntered past and said ‘Spot of trouble, sir?’ After Stephen had explained, the boy said ‘Easy! I go out with my Dad in the evenings, and do this all the time!’ The door was open in 15 seconds. Later, after he had moved to Mynyddbach, Shirenewton in Monmouthshire he taught at another school full of difficult children from deprived backgrounds near Newport (the steel industry was failing), he entered one apparently empty classroom on an upper storey to take the final lesson on a Friday, only to be greeted by a call from outside the window, and on investigation finding this class of boys hanging by their hands from the window-ledges. Rather alarmed, Stephen pleaded with them ‘do come in, PLEASE!’. Their spokesperson said, ’Only if we can leave a quarter of an hour early!’. Stephen, always one to compromise, agreed.

Outside school he was equally unconventional, One old friend wrote to me saying:

'Stephen always made me laugh and not to take things too seriously. Once we were taking a walk in the heart of the Hertfordshire countryside, A lady stopped us to ask the way. Stephen gave her directions using his map. We did not tell her the map was about 200 years old.'

He showed his love and understanding of my foibles as an eccentric older brother with a hilarious preface to my ‘Festschrift’, ‘Lets not bother with Lunch’ (pp.vii-ix in L. Gilmour (ed.), Pagans and Christians - from Antiquity to the Middle Ages, BAR Int.Ser,1610, Oxford 2007), in which he, a bemused younger brother, was diverted from the usual attractions of boyhood- and from his lunch (!), by my fanatic enthusiasm for snakes and other animals, old ruins and churches, and strange meetings with eminent archaeologists in megalithic tombs. Stephen’s fiction was often more to the point than what passes for truth. Nevertheless while he was still driving he took me everywhere, and we must have visited most of the churches, castles and Roman monuments in Monmouthshire and for miles around. Caerleon especially captured his imagination and featured in his fiction (see Stephen Henig, ‘Bringing Caerleon to life: archaeological reconstruction and the children’s novel’,pp.103-110 in C.Finn and M. Henig, Outside Archaeology. Material culture and the poetic imagination. BAR Int ser.2001,Oxford 2001).

One of his oldest friends summarised Stephen’s sterling qualities, recalling first the valiant manner in which he battled with ill health.

'His cheerful nature in any adversity was an example to me; he was always cheerful and straightforward. There must be many people who Stephen met in his life, who benefitted from his wise decisions and advice – his kindness in their difficulties.'

I can vouch for that in my own experience. But a great friend, then an undergraduate student still met Stephen when he visited me in Oxford. She wrote:

'He was very kind to me during a very miserable period of my life, helped me see things in perspective and I will never forget him.'

There must have been so many cases like that.

Stephen was a contented man; he spent his latter days listening to music, especially opera on which he was exceptionally knowledgeable. He loved nature films in particular and he so relished the view from the terrace of the house to the nearby woods, in one of which his ashes were laid to rest on 22nd October under a cloudless sky amidst the falling leaves and the birdsong.

Martin Henig (1955-1960)