Sir Christopher Foster (1943-1949)

Died on 18th February 2022, aged 91

Obituary from The Times on Saturday February 26th 2022 for Sir Christopher Foster, which was further subtitled “Influential economist who called out Tony Blair on ‘presidential’ government”.

Sir Christopher Foster’s distinguished career as an economist in Whitehall almost ended at birth when he crossed Barbara Castle.

The Oxbridge academic was considered a rising star after carrying out a brilliant cost-benefit analysis to justify London’s Victoria Line. The study outlined the social costs of road congestion if the line was not built and enabled London Transport to outmaneuvre the Treasury and secure funding.

Castle, the new minister of transport appointed him as her special adviser and chief economist in early 1966. At the same time, she planned to sack Thomas Padmore, her permanent secretary, something unheard of in Whitehall. Foster mentioned this in confidence over lunch to The Guardian’s political editor. When the story led the paper’s front page the next day, Castle was apoplectic. The dismissal was abandoned, but Foster also kept his job. He thought highly of Castle (“she worked hard and read every damned thing”) and she relied heavily on him when she carried through her complex Transport Act (1968).

Over the next four decades, governments of all hues would seek Foster’s advice. By the beginning of the 21st century, few could match his lengthy and varied experience of Whitehall and its environs.

Although a critic of Mrs Thatcher’s style, he supported her economic policies on privatisation and trade union reform. More controversial was his role in the poll tax, Thatcher’s ill-fated replacement for household rates in local government. He had co-authored Local Government Finance in a Unitary State (1980), which explored the possible benefits of a poll tax. Thatcher was determined to abolish household rates and Foster was invited to assess studies carried out by the Department of the Environment in 1985. He supported a poll tax when ministers ruled out other options and although critical of how it was implemented (particularly its regressiveness and the abolition of rates entirely), he provided momentum for it in Whitehall. He was knighted in 1986.

Foster voted Labour, except for a brief flirtation with the SDP in the 1980s, but was never partisan in his scrutiny of ideas. Between 1992 and 1994, he advised ministers on the privatisation of airports, electricity and telecommunications.

He continued to write prolifically, anatomising the drift towards presidential-style government in British Government in Crisis (2005). The acclaimed book chimed with growing sentiment in Westminster and in 2007 emboldened Foster, after decades of quiet influence, to publicly call Tony Blair “the worst prime minister since Lord North”. Although a supporter of many of New Labour’s policies, Foster deplored the decline of cabinet consensus and collegiality under Thatcher and Blair, ministers’ distrust of the senior civil service, reduction in deliberation and objectivity in policy analysis, and the increased reliance on spin doctors and special advisers.

He told the Daily Telegraph in 2007 that the trend had accelerated under Blair. “He’s lost us a form of government that creaked and groaned but worked reasonably well,” he said.

That year Foster was given the chance to recommend changes as the co-founder and chairman of the Better Government Initiative group, an elite corps of civil service mandarins, military top brass, academia and leading figures from the City of London to discuss how to restore trust in politicians. Few dissented from the group’s recommendations, but little action followed; Foster nodded when an admirer said he was a prophet without honour.

Christopher Foster was born in London in 1930. His father, George Cecil Foster, wrote some 80 novels and his mother, Phyllis (nee Mappin), was a Christian Science practitioner. With his irregular income from book royalties, which he usually overestimated, George moved the family home almost annually around North Kensington and Ealing during the 1930s. Christopher attended more than 20 primary schools, but settled and thrived at Merchant Taylors’ School.

After National Service as a platoon commander with the Seaforth Highlanders in Malaya between 1949 and 1951, he studied economics at King’s College, Cambridge and graduated with a first in 1954. While at Cambridge he met Kay Bullock, who was studying moral sciences. They married in 1958 and had five children: Henrietta, a BBC producer; Oliver, a child psychotherapist; Cressida, a teacher; Melissa, an NHS administrator; and Sebastian, a writer. All survive him.

He held research fellowships at Manchester and Oxford universities before an appointment as tutor in economics at Jesus College, Oxford, in 1964.

When Castle was transferred to the Department of Employment in 1968, Foster’s hopes of joining her were dashed. With the change of government in 1970, he returned to academe, heading a unit on urban economics. When Labour returned to office in 1974, he acted as part-time advisor to Anthony Crosland at the Department of the Environment and became director of the Centre for Environmental Studies (1976 – 78), where he began to develop his expertise in local government.

He gravitated to Conservative circles after 1979. By now he was in charge of the economics and public policy group at Coopers & Lybrand, becoming a director of the company in 1984. In these years Foster seemed to be everywhere. He served on the Megaw Committee into civil service pay, the Economic and Social Research Council, chaired the National Economic Development Office committee on the construction industry, worked with Michael Heseltine on the development of London’s Docklands and advised on the siting of the next generation of nuclear power stations.

Despite a courtier-like manner, Foster expressed his views frankly, no matter how inconvenient. Unlike many academics, he was eager to become involved in policymaking and to apply his ideas to the real world. He was also sympathetic to the pressures on civil servants and ministers. They in turn appreciated his practical turn of mind and for providing analysis not clouded in theory and equations.

A theatre and opera buff, Foster continued to write about government and finance into old age. Entering his nineties, he approved of Britain’s fast-shifting cultural landscape. A kindly man, he was a voracious reader, particularly of history, and adored the sort of secondhand bookshop where a bell rings when you open the door. Picking up a musty, out-of-print volume he would tell his companion how he had once met the author.

All judgements about politicians he had known and worked with were measured against his hero, William Gladstone. None quite measured up, but Foster admired Castle, Crosland, Heseltine and Shirley Williams. His house in Holland Park was filled with Gladstone memorabilia, 19th-centrury political cartoons and prints of the Crystal Palace; as a six-year old, he had witnessed the structure burning down.

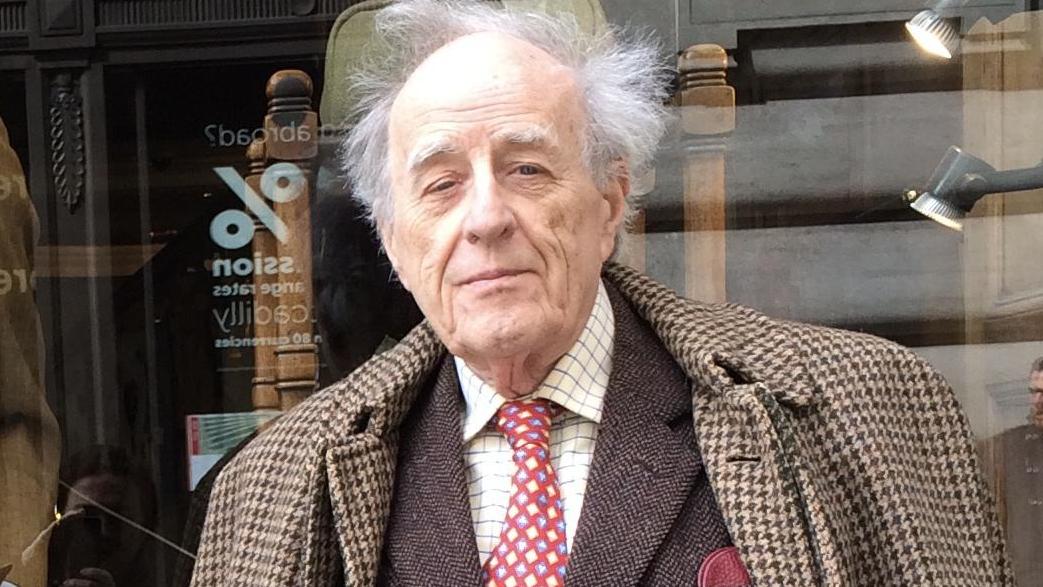

Casual wear was tweed, which he would buy from the same outfitter as his father and grandfather.

Proud of his Scottish heritage, he was a champion sword dancer in the Seaforth Highlanders. After Cambridge, he studied for a time at the University of Pennsylvania and was hitchhiking out of Philadelphia to a Highland dance in full tartan regalia when he was arrested for “impersonating a woman”. It took a call from the British Embassy to the police to explain traditional Scottish Costumes before Foster was released. The officer uncuffing him gave Foster a doubtful look before declaring: “I’m sure glad 1776 happened.”

Sir Christopher Foster, economist, was born on October 30, 1930. He died of frailty of old age on February 18, 2022, aged 91.